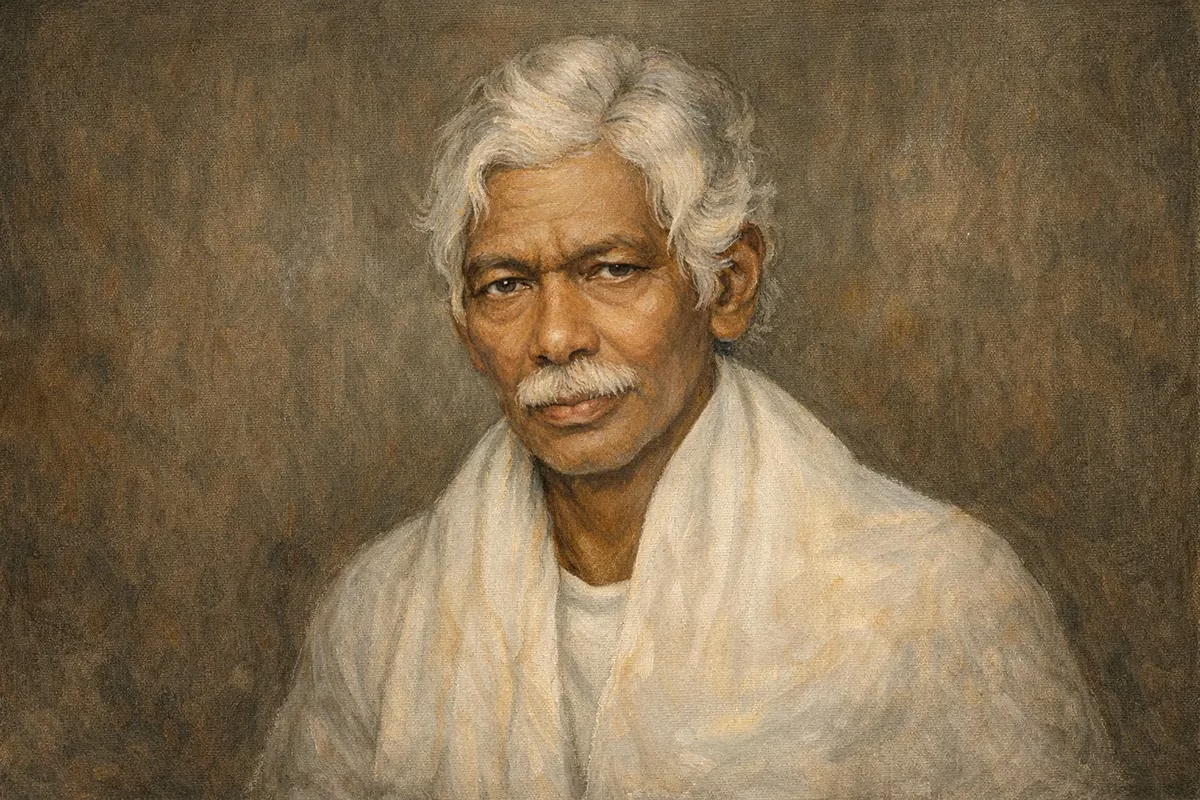

Raghunath Murmu: The Man Who Gave a Language Its Letters

The legacy of language is not limited to its scripting. It lives through songs, stories, and rituals, passing down from one generation to the next, even without a record. The Santali language also survived centuries through this one process. As a sound, it travelled through the years, but a language gets transformed over time if it is only verbally limited. Thus, a script is essential for its recognition and sustainability.

Santali language was alive verbally, but this changed in 1925 when Raghunath Murmu gave this language its alphabet, a means to survive time and generations. Among the many scripts of India, the script of the Santali language is a tale of patience.

A Life Shaped by Forests and Absence

Raghunath Murmu was born in 1905 in Dandbose village, in the sal forests of what was then the princely state of Mayurbhanj. Belonging to the Santal community, his life was shaped by sacred groves, harvest cycles, and memories shaped by oral traditions and cultures. When he was young, his local language was mostly spoken but not taught. It was taught through homes and generations, but never in the classrooms. It was sung in jahum dances, spoken in sarna rituals, and carried through folktales addressed to Marang Buru.

Formal education was rare for any Adivasi Language, and rarer for Santali. Murmu had to cross distances in order to attend a mission school where he could learn Bengali and Odia. But as he came closer to these languages, he realised that these languages were not purely different from the Santali language. There were sounds of Santali transformed, and the phonetics were significantly similar. To him, it seemed as if the Santali language was losing its meaning.

This birthed a discomfort in the heart of Raghunath Murmu. For him, his language was being borrowed and twisted into other languages, where it was eventually losing its true meaning. This pain associated him deeply with the lack of scripting that existed in the case of the Santali language.

When a Language Began to Ask for Form

When Raghunath Murmu grew up, he used to teach children in villages where he observed how the missionaries often used Roman letters in order to rewrite the Santali language. He further noticed that the administrators encouraged assimilation of Hindi. He could see the language no longer being remembered as the other scripts were getting integrated into it. This triggered an action. Because of Murmu, this was not just a linguistic loss but also a depreciation of the Santali Culture.

Thus, in 1925, at the age of twenty, Raghunath Murmu revealed the Santali Language Script he had been building. He named it Ol Chiki, which meant Santali writing. It was not borrowed or adapted but crafted fresh.

Crafting Letters from the World Around Him

The Santali Language Script he created, Ol Chiki, was built with intention. It consisted of thirty characters. The vowels were curved like water, eyes, and movement and the consonants echoed tools, animals, and trees familiar to Santal life. Written left to right, the script follows Santali phonetics closely, without forcing its sounds into borrowed forms. Among the many scripts of India, Ol Chiki stands apart for its clarity rather than ornament.

Resistance, Printing, and Quiet Spread

Murmu did not claim divine revelation. He tested the script patiently, teaching children, revising shapes, and writing early lessons on sal leaves. He printed his own grammar book, Lenjela, in 1931 using a hand-cranked press. Copies travelled quietly through bicycles, theatre groups, and village schools. Literacy grew not through institutions, but through use.

Writing as Cultural Memory

The resistance was real. British officials dismissed the script. Urban Santals leaned toward Roman letters. Yet Murmu continued writing. Over his lifetime, he produced more than 150 works, including primers, plays, histories, and songs. His writings documented Santal life without translation, allowing culture to exist on its own terms. For an Adivasi language, this was not scholarship. It was continuity.

Recognition Without Urgency

Recognition arrived slowly. Odisha adopted Ol Chiki in schools in 1975. Jharkhand followed in 1981. In 2003, Santali entered the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution. Murmu passed away before many of these milestones, having already spent decades travelling, teaching, and writing. His home in Dandbose now preserves notebooks marked by quiet persistence.

Within Santali culture, Ol Chiki is treated with care. It is written on walls, carried in belief, and protected through practice, not as myth, but as inheritance.

Century to a Structure

A century later, Ol Chiki entered the digital age. Manuscripts were archived. Learners enrolled online. The Constitution appeared in Santali script. For a language once confined to sound, this was alignment and not symbolism.

Raghunath Murmu offered choice and structure to not just a language but also a culture!

Disclaimer:

This content is for educational and awareness purposes only. Information may be interpretative, culturally influenced, or drawn from multiple sources. The Unknown India does not claim absolute accuracy in all cases.